Last week I walked around Plainfield Township Cemetery taking pictures, reading tombstones, and meditating on the meaning of this weekend of Halloween, All Saints Day, and All Souls Day when we celebrate the lives of people who have gone before us. I asked many questions about who were these people? Some of the names you may recognize as multi-generational families in this church. You might even be as part of one of those families. Some names you may recognize because streets around here are named after them, like Van Dyke and Book. I have some sense of what life was like in the 19th century, but I thought about these specific people buried beneath my feet. What were their lives like? What were their hopes and dreams for their future generations? What was their vision of the future? As strange as it may sound, I had an encounter with them through their graves, their dates, their dashes, their epitaphs.

Ever since the Industrial Revolution and the accelerating progress of technological advancement, we have become experts at separating one generation from another.

Back in my day, we didn’t have the internet!

Back in my day, we didn’t have calculators!

Back in my day, we didn’t have television!

Back in my day, we didn’t have radio!

Back in my day, we didn’t have cars!

Back in my day, we didn’t have trains!

Think about the rapid changes of the 19th century when those people lived who are buried in the cemetery. Take a field trip to the I&M Canal Museum in Lockport some day. In the mid 19th century the Canal was one of the world’s largest construction projects, providing passage for cargo from the new city of Chicago to the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico and then to the world. Yet the centrality of its importance for commerce in this region lasted only about 20 years because the railroads quickly took over much transportation of freight.

Can you hear those cross-generational conversations, from a century ago?

When I was a boy, I whipped that mule up and down the Canal and earned a buck a day!

Wow, grandpa, that was a lot of work, pulling those boats, even just one mile. Now I drive a train at a mile a minute and haul a hundred times as much freight!

I’m sure it’s not hard for you to conjure up similar conversations you have with people, younger or older than you, about the vast changes in recent history. What’s your default position when talking to someone from a younger generation? They’re naive? They don’t know what real work is like? What’s your default position when talking to someone from an older generation? They’re change resistant? They don’t appreciate how complicated things are now?

Whatever is your default position when dealing with someone from a different generation when there’s a clash of cultures, you’re likely operating from what I would call our “prophetic” instinct. You’re trying to warn them about something that doesn’t seem quite right to you, about something that seems discontinuous from how things should be. This sense of duty to warn the other should not come from a sense of superiority but from a positive vision of the future. When speaking prophetically we must have a healthy vision for the future to accompany our critique of what’s wrong now. That’s what makes a prophet distinct from a crank. Vision. A positive vision of a more just future.

We know very little about the prophet Habakkuk. We think he lived in Jerusalem in the time before the Babylonians laid siege to the city and completely conquered it in 586 BCE. This was the same time that the prophet Jeremiah was active. Reading these prophets now can seem difficult because so much of what they preached was contemporaneous to the “what’s wrongness” of their times. Foreign powers are amassing again, and it looks like they’re going to destroy and enslave us. That’s the gist of what you need to know when reading much of the prophets. That’s the disturbing background of Habakkuk. What is so compelling about Habakkuk in the passage we heard this morning is that his prophetic critique of what’s wrong is not the voice of God calling out to the leaders of the day, it’s the voice of Habakkuk calling out to God!

O Lord, how long shall I cry for help,

and you will not listen?

Or cry to you “Violence!”

and you will not save?

Why do you make me see wrongdoing

and look at trouble?

Destruction and violence are before me;

strife and contention arise.

So the law becomes slack

and justice never prevails.

The wicked surround the righteous

therefore judgment comes forth perverted.

What is God’s response? Well, in addressing the why me? cry of Job, God essentially says, “Who are you to question me about the way things work? You’re puny compared to the whole of creation!” To Habakkuk God’s response is much more constructive: “Write the vision; make it plain on tablets … For there is still a vision for the appointed time; it speaks of the end, and does not lie … Look at the proud! Their spirit is not right in them, but the righteous live by their faith.”

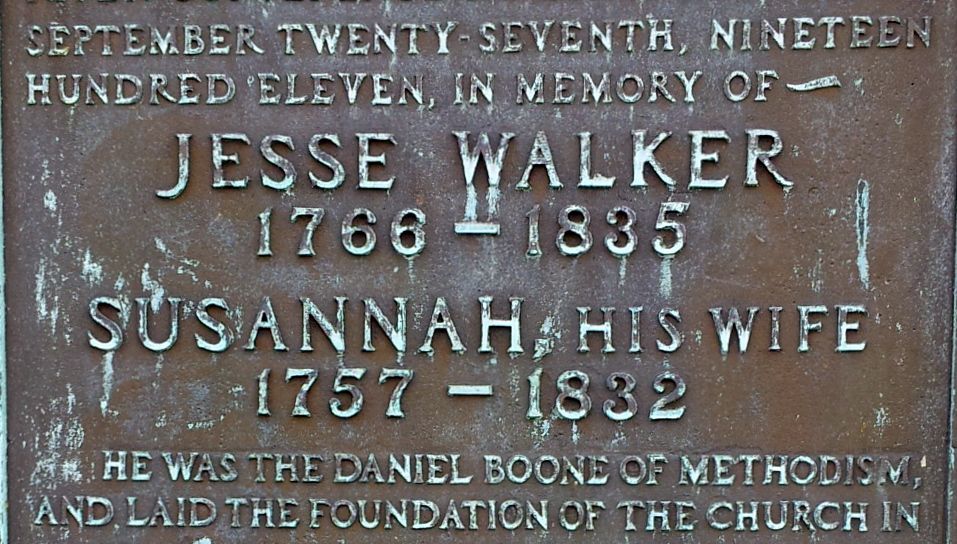

If you walk around Plainfield Township Cemetery, what vision of the future do you encounter through the graves, the dates, the dashes, the epitaphs? I thought about the envisioned future of the settlers of this area implied by the epitaph of a woman who died in 1876: “Mother of the first white child born in Will County.” That was obviously an important thing to commemorate for a family who lived on the edge of the frontier in the first half of the 19th century. The day before my visit to the cemetery I visited Settlers’ Park and read about how those settlers displaced the native peoples of this region. The settlers’ vision for the future is now transcended by our present realities, yet their vision and our reality are yoked. When this church was started in 1829 by the circuit rider Jesse Walker, the state of Illinois had passed a law banning marriage between people of different races. Our present reality transcends their future.

To transcend those past futures, we need to “be righteous” and “live by faith,” as the prophet preaches. The two, “righteousness” and “faith,” are inextricably linked. Righteousness without faith in God’s ongoing transformation of the world is often little more than hypocrisy, thinking that our time-bound ideals are the ends of transformation, instead we and our ideals are merely the temporary means for transformation. We inherit so much “righteousness” and “faith” from previous generations, but we must embrace the newness of the “spirit of wisdom and revelation,” as named by the writer to the Ephesians. Why? “So that, with the eyes of your heart enlightened, you may know what is the hope to which he has called you, what are the riches of his glorious inheritance among the saints, and what is the immeasurable greatness of his power for us who believe, according to the working of his great power.”

This All Saints Sunday, let us look in the mirror. Let us look at what we have inherited from previous generations. Let us embrace those previous generations for transmitting to us the “faith which was once for all delivered to the saints,” as the Apostle Jude put it in his epistle. But let us not be content with their faith. Let us keep on perfecting the faith by encouraging future generations to transcend our faith, in the “spirit of wisdom and revelation” so that Christ’s “immeasurable greatness” is done here on earth as it is in heaven. Amen.