Have you ever heard of “escape rooms?” They are a global phenomenon and a growing segment of the gaming industry. Stuart Miller, writing for Newsweek, succinctly explained the game: “Room escape games lock players in a room where they must seek clues and solve puzzles tied to a story or theme to escape before time runs out, usually in one hour.”

Have you ever heard of “escape rooms?” They are a global phenomenon and a growing segment of the gaming industry. Stuart Miller, writing for Newsweek, succinctly explained the game: “Room escape games lock players in a room where they must seek clues and solve puzzles tied to a story or theme to escape before time runs out, usually in one hour.”

Is the UMC trapped in a giant escape room?

Like many in the UMC, I am concerned about the escalating tension and anxiety in the UMC regarding a possible split. This is nothing new, however, as divisions and conflict within the UMC have been simmering since the very beginning of the denominational merger that created the UMC in 1968.

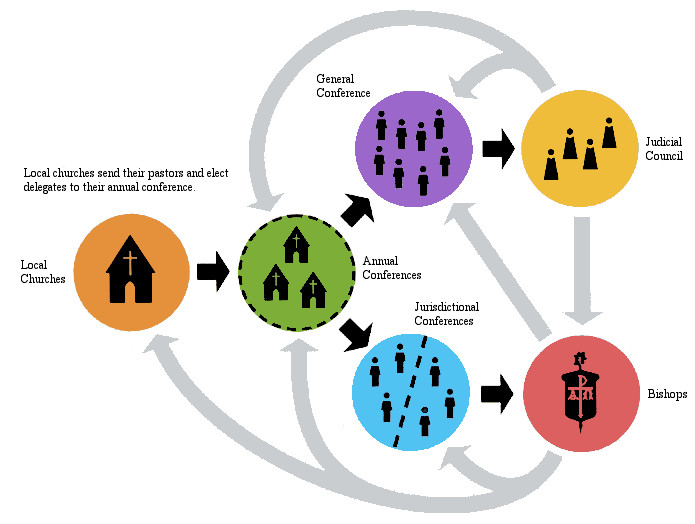

In a real sense, the UMC is already divided, more than by political and theological views, though that is true, but rather the UMC is and has always been “divided” … by design. You may think the UMC is “vertically integrated,” like a giant corporation that manufactures all of its own parts, assembles them as products, and then markets, sells, and distributes those products. The UMC is not vertically integrated like a corporation. Rather, the UMC is “connectional.” The UMC.org website explains the higher level structure of the UMC: “The United Methodist Church does not have a central headquarters or a single executive leader. Duties are divided among bodies that include the General Conference, the Council of Bishops, and the Judicial Council. Each of these entities is required by our Constitution, a foundational document, to be part of our structure, and plays a significant role in the life of the church.” One of the most significant elements holding together the connection is the Book of Discipline. When the Discipline eventually gets around to talking about how mission and ministry actually happens, it starts this way:

The mission of the Church is to make disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world. Local churches provide the most significant arena through which disciple-making occurs.

This primary focus on individual followers of Jesus Christ and the local church as “the most significant arena through which disciple-making occurs” gives me great hope for the future of (United) Methodist faith and practice. This is how the church works, from the ground level up, from the hopes and dreams, from the dedication and work of individuals in local church communities outward to the world. The vast majority of the words in the Discipline concern the “top” tiers of the UMC with its various connections and structures. However, as with the Bible, we should discern and prioritize the incarnational over the institutional. This is not to say that institutions are not important and valuable; it is to say that institutions serve the fruitfulness of persons living together and not institutional self-preservation for its own sake.

In the Gospels we encounter Jesus orienting his mission and ministry in this way, by turning upside down the institutional power structures of his day by incarnationally favoring the least, the last, and the lost, as testified to in the Sermon on the Mount, especially the Beatitudes, and so many of his parables. What, then, is the purpose of organizing ourselves into groups? Into institutions? The purpose is simple, really. Our institutional purpose is to learn how to actually live together, a purpose made plain in the “Episcopal Greetings” of the Discipline:

The Discipline of The United Methodist Church is the product of over 200 years of the General Conferences of the denominations that now form The United Methodist Church.

The Discipline as the instrument for setting forth the laws, plan, polity, and process by which United Methodists govern themselves remains constant. Each General Conference amends, perfects, clarifies, and adds its own contribution to the Discipline. We do not see the Discipline as sacrosanct or infallible, but we do consider it a document suitable to our heritage. It is the most current statement of how United Methodists agree to live their lives together. [emphasis mine]

I will not pretend to offer solutions to keep our connection connected. Christian history is full of church “splits.” After all, this is how everything survives and grows, by dividing and multiplying. We should expect division, even (especially?) with the church. I sense what you are thinking and asking yourself, “Are not Christians to be of one mind?” Yes, but what does that mean? “Finally, all of you, have unity of spirit [KJV: “be ye all of one mind”], sympathy, love for one another, a tender heart, and a humble mind” (1 Peter 3:8).

Christians in the UMC need to find more fruitful ways to talk about and work out our connectional future together, rather than obsessing with intractable political and theological differences. We may never find a way to wordsmith the Discipline to mollify, let alone satisfy, the concerns of divided groups within the UMC and still hold it all together. I want to ask, though, is that really the issue? The language of the Discipline? Even if we change the language of the Discipline, will our divisions end? Will our impoverished imagination of life together as a collection of disparate political interests end?

The real issue isn’t language in the Discipline.

The real issue is hardness of heart and that we lack imagination when it comes to actually living together with real divisions among us. The church is not alone in its fearful lack of imagination. The United States of America and nations all around the world are going through turmoil and are having a hard time imagining what comes next in history.

We do not need to “solve” the political puzzles of our grand escape room, only to enter yet another room with its own political puzzles and anxieties.

We should appreciate our connectedness as a way of being, which has deeper meaning than viewing our connectedness as a system of institutional connections to be maintained. We need faith and imagination to see why we would need institutional connections in the first place. We need the faith of Jesus on the cross in Luke 23:34 when he said, “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.” But we seem to be ignoring forgiving faith and instead are living more in the next part of that same verse: “And they cast lots to divide his clothing.”

Metaphors for Institutional Imagination

I want to suggest two metaphors for imagining our institutionalized life together that, I hope, will help provide a different perspective on how we’re treating each other in the midst of escalating tension and anxiety. These metaphors are inspired by two objects from medieval and agrarian Europe.

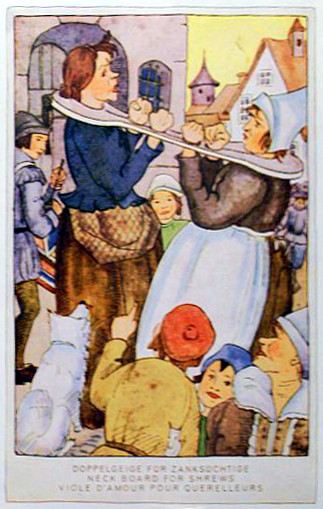

In the summer of 2015 my family and I were on vacation in Europe and spent a couple of days in Rothenburg ob der Tauber in Bavarian Germany. Rothenburg is a well-known tourist town, famous for preservation of its medieval old town. One of the tourist sites is the Kriminalmuseum, a museum of medieval crime and punishment. Among the artifacts there is the “double-neck violin,” in which two bickering people would be locked together, face-to-face, and would not be released until they reached agreement.

In the summer of 2015 my family and I were on vacation in Europe and spent a couple of days in Rothenburg ob der Tauber in Bavarian Germany. Rothenburg is a well-known tourist town, famous for preservation of its medieval old town. One of the tourist sites is the Kriminalmuseum, a museum of medieval crime and punishment. Among the artifacts there is the “double-neck violin,” in which two bickering people would be locked together, face-to-face, and would not be released until they reached agreement.

The other object is a yoke to hold together strong animals to help plow the fields, guided by a farmer. The First UMC of Elmhurst has such a yoke hanging in their main entry area, a yoke that came from Germany with the family of UMC pastor Arthur Landwehr, who served FUMC of Elmhurst 1969-1975.

The other object is a yoke to hold together strong animals to help plow the fields, guided by a farmer. The First UMC of Elmhurst has such a yoke hanging in their main entry area, a yoke that came from Germany with the family of UMC pastor Arthur Landwehr, who served FUMC of Elmhurst 1969-1975.

These two objects are not dramatically different. They essentially serve the same physical purpose by locking together two creatures by their necks. However, their non-physical (spiritual) purposes are quite different.

The double-neck violin locks together two bickering persons so they can work it out. Why? Because, presumably, they disrupt their social environment, and their disruption must be quite extreme to use such a tortuous device. Note that someone with authority must have the power to lock them into the device to maintain social order. I wonder how many disagreements were actually solved with the double-neck violin?

The double-neck violin locks together two bickering persons so they can work it out. Why? Because, presumably, they disrupt their social environment, and their disruption must be quite extreme to use such a tortuous device. Note that someone with authority must have the power to lock them into the device to maintain social order. I wonder how many disagreements were actually solved with the double-neck violin?

The farmer places the yoke around two strong animals to leverage their power to achieve a common good, the tilling of soil for the planting and cultivating of new life. The animals may be strong-willed. They may not like the yoke. They may even not like each other. But that is irrelevant to the larger, spiritual purpose of their common effort for the farmer. The yoke makes it possible for the two animals to walk side-by-side, even while fighting each other, pulling this way and then that. Nevertheless, they walk side-by-side and pull the plow as guided by the farmer who will later plant seeds, cultivate crops, and reap the harvest.

In Matthew 11:28-30 Jesus said, “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.”

Double-neck violins perpetuate us looking inward.

Yokes propel us to look forward.

United Methodists, it’s up to you to imagine our way forward. Are we going to imagine our connection as a double-neck violin that we’re stuck in? That we can’t take it anymore? That we just want to be released from each other? Or, are we going to imagine ourselves yoked together? We may be exhausted, trying to pull each other in our own direction. But …

We are yoked together, pulling forward for the greater good.

Use your imagination. You decide how we go forward. We are connected to each other. In fact, we are connected to everyone else and everything else on this speck of a planet. To be released from the device of your imagination will not solve anything because you will soon find yourself locked into a new device, whether you like it or not; that’s the nature of being human. We’re all in this thing called “life” together.